SEZs along Belt and Road encourages growth in frontier regions (Africa focus)

A Model for Growth in Frontier Regions

A Model for Growth in Frontier RegionsChina began developing special economic zones (SEZs) in the early 1980s as part of Deng Xiaoping’s drive to accelerate development.

More recently, SEZs have become a key component of the Belt and Road initiative (BRI), with many countries along the BRI looking to such zones to help achieve the same kind of economic growth witnessed in China. Chinese companies in turn are looking to replicate the sustained domestic growth they achieved via the SEZs beyond China’s borders.

SEZs have been important drivers of China’s economic success, contributing an estimated 10 per cent of the country’s GDP since the days of Deng Xiaoping.

As designated geographical areas where foreign and domestic companies could trade and invest without being subject to the same controls and regulations applied in the rest of the country, SEZs were designed to encourage investment and boost economic growth in China.

As designated geographical areas where foreign and domestic companies could trade and invest without being subject to the same controls and regulations applied in the rest of the country, SEZs were designed to encourage investment and boost economic growth in China.

One of the first, Shenzhen, epitomises the success of the Chinese SEZ model: over the past 35 years, it grew from a small town into a major trade hub and one of China’s biggest cities.

The initial success of the SEZs led the Chinese government to sanction specialised ‘Economic and Technological Development Zones’ that emphasised high-tech research and development industries. More recently, the establishment of SEZs has been encouraging technological advances along the Belt and Road.

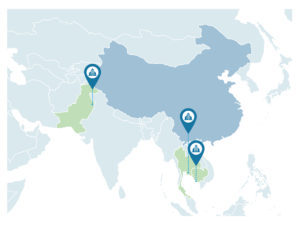

Long before BRI was announced, China was encouraging its firms to take advantage of the incentives offered in SEZs and industrial parks outside of China. Among the first locations to be approved by the Chinese government for its state-owned enterprises to establish a presence overseas were the Sihanoukville Port in Cambodia, the Haier-Ruba in Pakistan and the Rayong Industrial Park in Thailand. Since its inception in 2005, the latter has built up a cumulative industrial value of USD8 billion.

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, by April 2018 construction had been started or completed on 56 economic cooperation zones in 20 BRI countries, with Chinese companies investing more than USD18.5 billion in such zones along the BRI. The zones are estimated to have generated over USD1 billion in tax revenue for host countries and created around 177,000 local jobs.

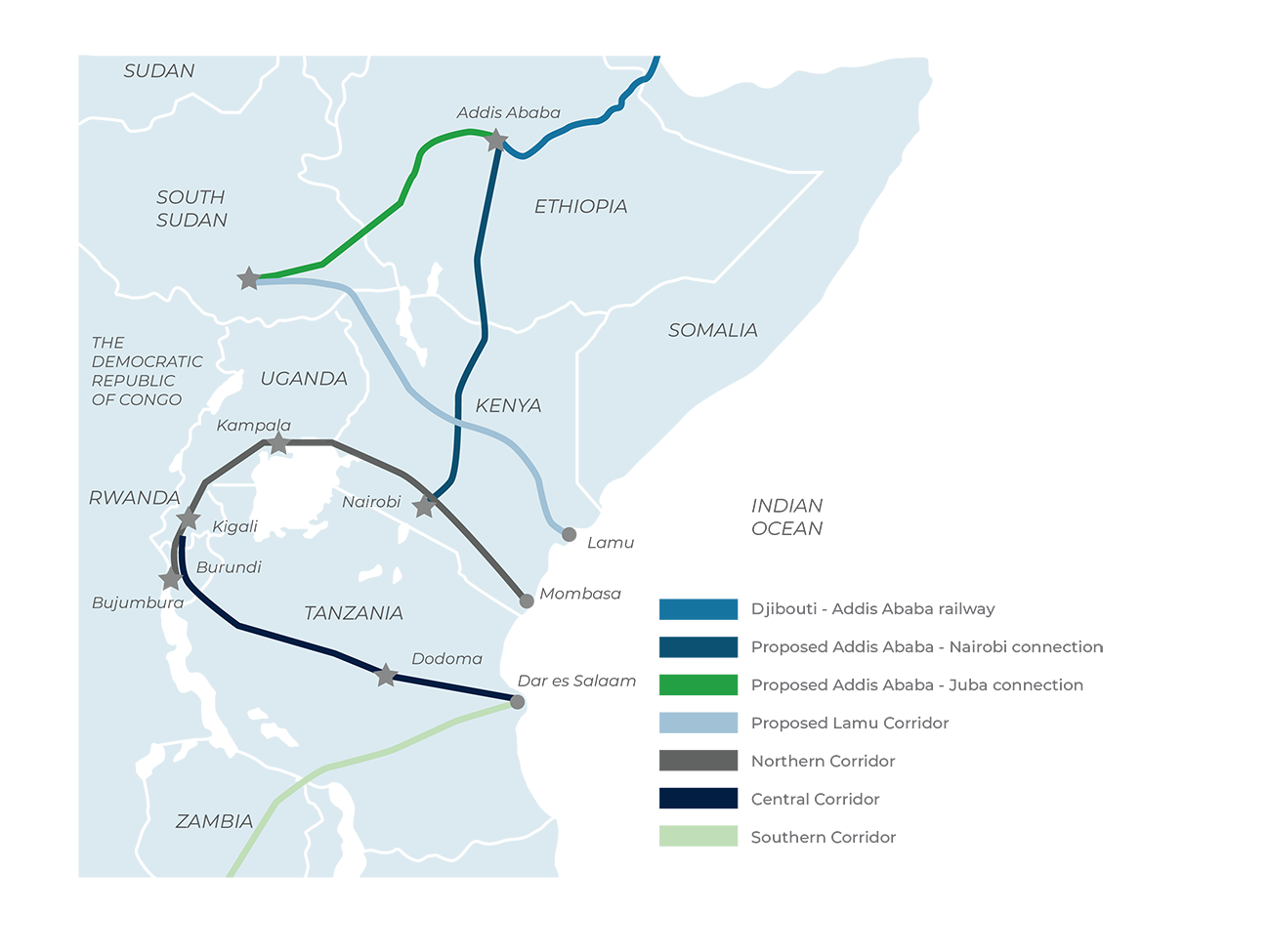

These zones are located across BRI corridors; through South-east Asia, across Eastern Europe, and along both the east and west coasts of Africa. Some of the newest zones have been set-up in Kenya, the latest country to join Africa’s SEZ boom, and in Belarus, which is building the huge Great Stone Park – a statement of ambition for both Belarus and China. Both have different yet important implications for future SEZs along the Belt and Road.

China’s ‘Going Global’ policy, (also known as the ‘Going Out’ strategy) emerged in 1999, paving the way for expansion in regions that subsequently became defined as BRI routes – particularly in Africa. A main objective was the establishment of economic and trade cooperation zones abroad, with African nations encouraged by how economic zones were creating prosperity in China. Subsequently, Egypt, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Nigeria and Zambia were quick to establish SEZs, attracting investment from China and elsewhere.

Most recently, Kenya announced plans to establish several SEZs near the sea ports of Mombasa and Lamu, and at the Lake Victoria port of Kisumu. The Lamu SEZ forms part of the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (Lapsset) Corridor, a regional project touted since the 1970s that is finally being developed. At Lamu, construction is underway on an oil pipeline to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, a deep-water 32-berth port, a new international airport, road and rail connections to South Sudan and Ethiopia, and a ‘resort city’.

Kenya also has authorised the development of private SEZs on land concessions granted to foreign companies. In mid-2017 China’s Guangdong New South Group broke ground on a 700-acre site at Eldoret in eastern Kenya’s Rift Valley. Known as the Pearl River SEZ, the USD2 billion smart city project is being developed with a local partner and is scheduled for completion in 2019. The partners say the SEZ will consist of three different sections: an industrial park, a science and technology park, and a zone for commercial, residential and recreational development. Interest is expected from sectors as diverse as medical tourism, wildlife conservation, film and entertainment, and manufacturing.

Kenya also has authorised the development of private SEZs on land concessions granted to foreign companies. In mid-2017 China’s Guangdong New South Group broke ground on a 700-acre site at Eldoret in eastern Kenya’s Rift Valley. Known as the Pearl River SEZ, the USD2 billion smart city project is being developed with a local partner and is scheduled for completion in 2019. The partners say the SEZ will consist of three different sections: an industrial park, a science and technology park, and a zone for commercial, residential and recreational development. Interest is expected from sectors as diverse as medical tourism, wildlife conservation, film and entertainment, and manufacturing.

Kenya’s previous attempt to develop industrial and business parks – export processing zones (EPZs) that were promoted in the early 2000s – failed to provide the returns anticipated. The decision to adopt the SEZ model, similar to that used in China, is expected to be more successful due to its timing, with the ability to connect the new zones to BRI corridors across Africa and beyond.

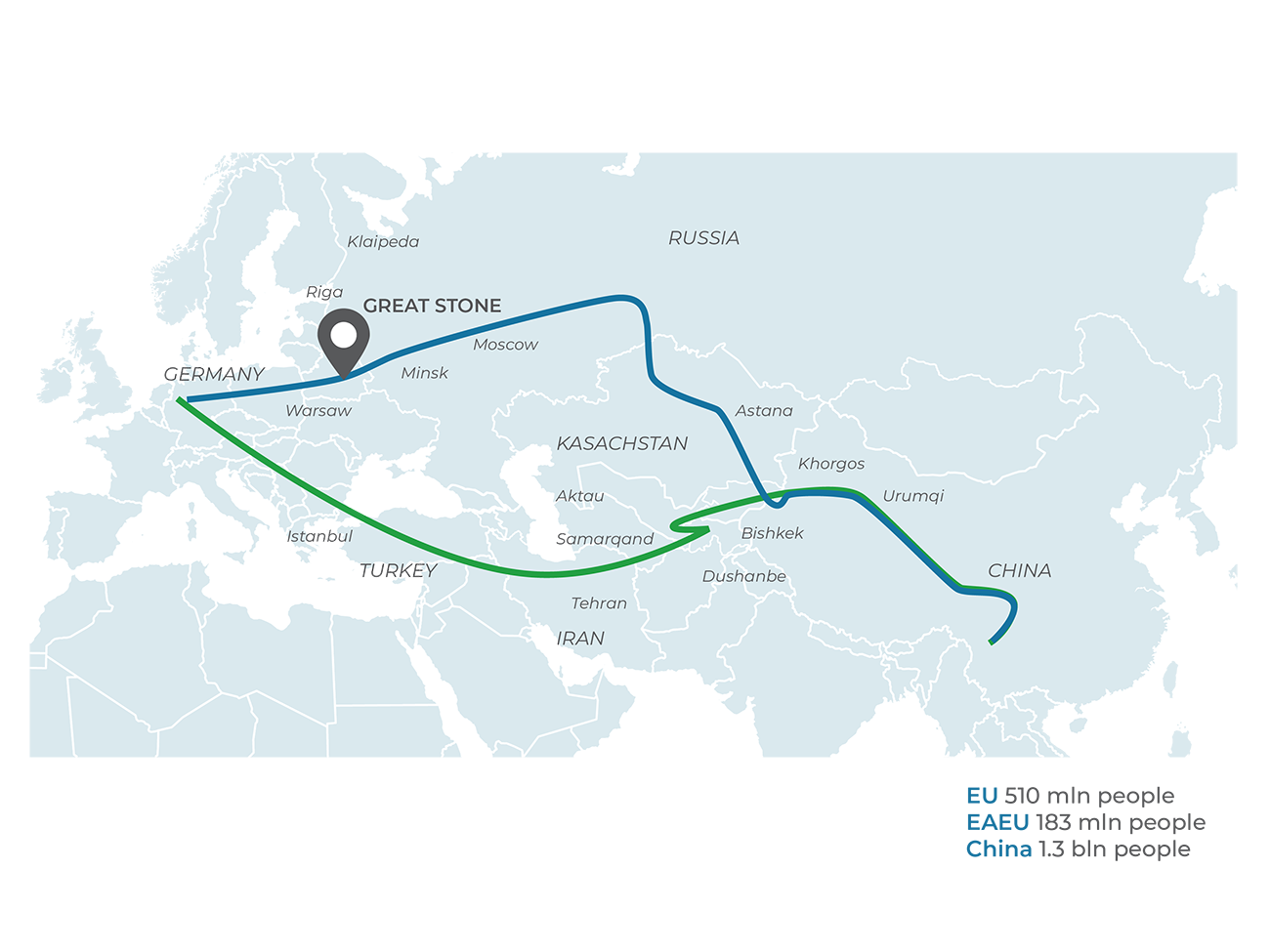

“If we succeed here, we will succeed everywhere,” said China’s Vice President, Wang Qishan, on his visit to the China-Belarus Great Stone Industrial Park in May 2018. Such is the scale of the park that it is seen as crucial to the success of the whole BRI.

Situated at the geographic centre of Europe, 25km outside the Belorussian capital of Minsk, Great Stone is the largest European industrial park to be established under BRI, occupying around 80 square kilometres and surrounded by a forest reserve. First mooted in 2010, it is a crucial part of China’s drive to establish production bases and logistics hubs in Eastern Europe, and improve access to the Eurasian Economic Union and the European Union markets. Chinese officials have dubbed the park “the pearl of the Silk Road Economic Belt”.

With close access to Minsk National Airport, railroads, and the Berlin-Moscow transnational highway, the park is expected to attract USD30 billion worth of foreign investment. By July 2018, almost USD1 billion had reportedly been spent by companies setting up in the park. German, Belarusian and Chinese firms are expected to start work on a logistics hub, including rail connections, by the end of 2018, by which time an expansion to the nearby airport should also have been commissioned.

Both Belarus and China see this as a long-term project that will take around 30 years to complete, with individual areas of the park opening as they are ready. Great Stone is designed with several zones: an industrial area, a financial centre, a research and development sector, a trade zone, an office area, plus a residential town with accompanying infrastructure and entertainment premises. China has given more than USD1.1 million in aid towards facilities for residents of the park, and the Belorussian government has predicted that 10,000 people will work and live there by 2020, growing to more than 130,000 by 2030.

Whether an SEZ is located in Africa or Eastern Europe, the goal is the same: countries in these regions are looking to attract investors by providing bundles of incentives in strategic locations. And as the Kenya and Belarus examples demonstrate, the emergence of SEZs along the Belt and Road is driving benefits for both the hosts and the investors. The former benefit from tax breaks and better communications links and facilities – as well as ancillary benefits such as job creation.

As with most BRI projects, China has taken the lead, backing the development of these SEZs by encouraging its companies to move into the zones. This not only supports its ‘Going Global’ ambitions; it promotes beneficial synergies – for example in markets like Kenya and Belarus. Businesses get the opportunity to supply complementary services and goods to each other, attract a large and versatile workforce, and share the costs of basic needs. SEZs spur foreign investment, build infrastructure, and help host countries diversify their economies. As more companies move in, costs should decrease as opportunities grow – a model for success that can be replicated across the Belt and Road.

As with most BRI projects, China has taken the lead, backing the development of these SEZs by encouraging its companies to move into the zones. This not only supports its ‘Going Global’ ambitions; it promotes beneficial synergies – for example in markets like Kenya and Belarus. Businesses get the opportunity to supply complementary services and goods to each other, attract a large and versatile workforce, and share the costs of basic needs. SEZs spur foreign investment, build infrastructure, and help host countries diversify their economies. As more companies move in, costs should decrease as opportunities grow – a model for success that can be replicated across the Belt and Road.

This article was also published on Bloomberg.com.