What does Belt and Road mean for the shipping industry

About 90 per cent of the world’s trade is carried by ships, simply because it’s the most cost-effective way to move bulk raw materials and finished goods. As a result, the shipping industry is often seen as a barometer of global economic health.

Before the global financial crisis in 2008, dry-bulk shipping rates had hit an all-time high, and orders for new container ships were at record levels. Even though the crisis hurt the industry, freezing orders and sending rates plunging, by 2013 carriers were back building ever-larger vessels in unprecedented numbers.

Then, in August 2017, South Korean giant Hanjin Shipping Co. collapsed, upending the industry in much the same way that Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy roiled the financial sector nine years earlier. One of the world’s largest shipping firms at the time, Hanjin folded in the face of a cash crisis as supply outstripped demand, weakening pricing power and decimating profits for carriers.

For an industry facing a squeeze, will the blossoming of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) redefine trade routes, unlock new opportunities and revitalise the maritime industry? Or will the explosion of terrestrial infrastructure under the initiative and another expected associated surge in shipbuilding have an adverse effect on the market?

The Maritime Silk Road – connecting China with South-east Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe – is a critical part of the overall vision for BRI, and to that end China has been pouring money into boosting shipping capacity.

In 2017, Chinese banks invested USD20 billion in ship financing, 33 per cent more than the year before. This ongoing surge in investment coincides with a period when many European banks that were once heavyweights in ship finance – such as Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds and HSH Nordbank – are pulling back from the business.

Chinese lender ICBC saw its ship-financing portfolio grow from less than USD500 million in 2009 to USD10 billion in 2017. Chinese financiers – mainly the big five of ICBC, Minsheng, Bank of Communications, China Merchants Bank and China Development Bank – now account for a quarter of the sector, according to Marine Money research.

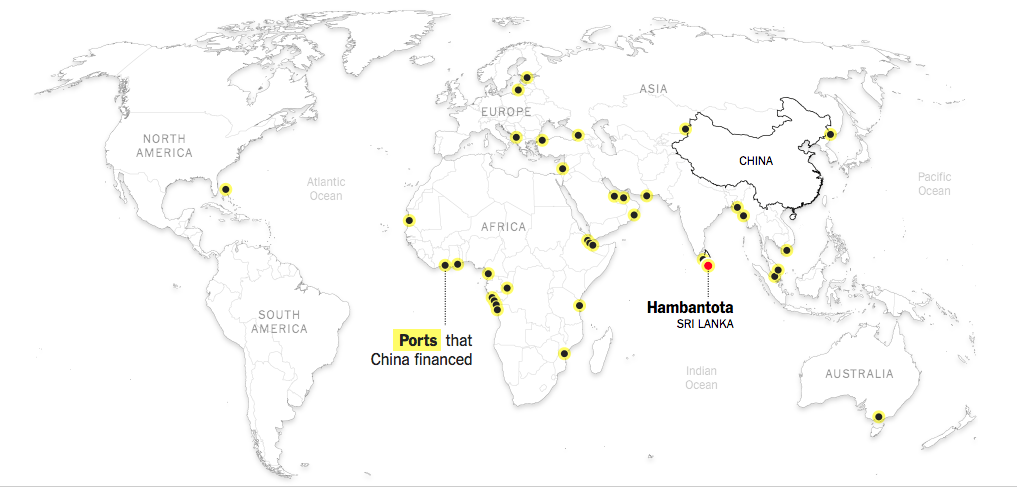

China has also invested an estimated USD20 billion in port infrastructure in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe in the past two years. Most of this has gone into building and upgrading container terminals to accommodate larger vessels.

At home, the ports of Ningbo-Zhoushan and Xiamen have seen dramatic growth. Under the umbrella of BRI, China has made strategic investments in ports in Djibouti, Athens (Piraeus) and Hambantota in Sri Lanka, enlarging facilities and introducing new technology to reduce handling costs. China has also financed the development of Kuantan and Samalaju ports in Malaysia. In Pakistan, China has committed about USD46 billion to create the port of Gwadar, the terminus of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that gives China direct access to the Indian Ocean.

As trade grows and infrastructure projects mushroom under BRI, increased demand for shipping has been one of the more immediate consequences, easing some of the industry’s overcapacity problem. These projects require enormous quantities of iron ore, steel, cement, heavy machinery and other materials, and the most cost-effective way to transport materials is by sea.

Under BRI, capacity at key ports along the Maritime Silk Road has been expanded (or created from nothing) and logistics have been upgraded. Once in place, these new and improved ports will have opened up fresh trade routes and expanded existing ones.

The port in Djibouti (East Africa), for example, links to Ethiopia by a railroad also constructed under the BRI umbrella, with approximately 70 per cent of Ethiopia’s foreign trade expected to channel through Djibouti.

The opening of Gwadar put the finishing touches on a new trade route that stretches from western China and Central Asia, through South Asia and out to the wider world. The first commercial shipment left Gwadar in March 2018, carrying containers of Pakistani seafood to Dubai.

In Xiamen Port in Fujian, a USD335 million upgrade resulted in a free-trade zone and new domestic and international trade-transit centres. The port now operates five onward freight-train services to Europe for goods brought by sea. Elsewhere, the Ningbo-Zhoushan Port has become the busiest in China. New markets opened up by the BRI have boosted the number of sea routes operating from Ningbo to 86.

“The level of planned BRI investment will require a sound legal framework that embraces regulatory requirements, cultural considerations and dispute resolution. The initiative also provides nations with the incentive to develop their own institutional arbitration and mediation mechanisms.”

Just as overland BRI trade routes will require new streamlined customs, legal and technological regimes to smooth commerce, so too authorities along the maritime routes will need to negotiate new freedom-of-navigation agreements and legal frameworks to cope with anticipated heightened trade. This could herald a new era of trade cooperation.

Amid the optimism surrounding new ports, capacity upgrades and increased trade, there are concerns that the impact of the BRI will not be uniformly positive for shipping.

In the wake of the Hanjin collapse, a massive industry consolidation escalated:

The growing use of mammoth ships has been an important factor in the turnaround. Companies who own them are able to deploy fewer vessels and move more cargo on a single journey to benefit from higher rates. However, some industry observers are concerned that China’s heavy investments in new shipping may prolong oversupply issues and delay the industry’s recovery.

There are about 58 ultra-large carriers worldwide that can transport more than 18,000 containers each, and their number is expected to double in two years.

The shakeout of the crisis has been less kind to operators of smaller vessels, and port developments along BRI routes may exacerbate that situation by encouraging the use of larger ships through increased capacity, faster logistics and more efficient technology.

In some ways, the overland belt and maritime roads are in competition. The Eurasian Land Bridge road and rail routes through Central Asia to Europe, for example, will only become quicker as technology and multilateral cooperation dismantles the logistical hurdles that slow them down. That could encourage the shipment of high-value, time-sensitive goods that would otherwise be moved by sea. Equally, the expansion of the highway network from China through Central Asia and Central Europe may also encourage smaller exporters to switch away from maritime transport.

The establishment of strategic energy pipelines through Asia also provides an alternative to crude-oil and LNG shipping. The pipelines connecting Kunming in Yunnan province and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar cut the distance oil needs to travel from Africa or the Middle East by about 700 miles (1120 kilometres), reducing the need for shipping. The Myanmar-Chonqing gas pipeline may have a similar effect.

Any restraining factors, however, are likely to be more than counterbalanced by a surge in global trade.

“What’s really interesting is the synergy between the ‘Belt’ and the maritime ‘Road’ as evidenced by the development of Gwadar Port in Pakistan by COSCO – where the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor provides a distribution platform for maritime access to global markets,” said Nigel Anton, Global Head of Shipping Finance at Standard Chartered. “With developments like this, the Belt and Road initiative is already having a positive impact on the maritime and port logistics industries. This will only grow in the years ahead.”

This article was also published on Bloomberg.com.