The butterfly effect of the supply chain

You’ve probably heard of the term ‘the butterfly effect’. It was proposed by American meteorologist Edward N. Lorenz who theorised that a butterfly gently flapping its wings in Brazil can set off a chain of events that eventually cause a hurricane halfway across the world in Texas. Global supply chains are similarly interlinked. Their complexity and interdependency mean that one small change can snowball into momentous impact.

Today’s supply chains must be robust and flexible enough to handle an increasingly volatile market (particularly during COVID-19) while meeting the ethical standards that educated consumers demand. Yet a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit on global supply chains, commissioned by Standard Chartered, found that executives had unwarranted confidence about how responsible their supply chains were, with some allowing supply chain responsibility to slide as a priority in the past five years.

So what does the butterfly effect look like in the world of logistics, and how can a stronger, more responsible supply chain be forged? As it turns out, it all starts with you.

Imagine you’re standing in a grocery store aisle, looking at a dozen different jars of peanut butter. As a modern-day shopper who wants to support sustainable environmental and work practices, you pick the one that says “ethically sourced” or “pesticide-free”.

In this scenario, you’re one consumer among millions. But you’re not alone. A 2019 US Consumer Sustainability Survey found that 70 per cent of respondents consider sustainability when making a purchase and nearly half don’t mind paying extra for a more sustainable product.

When enough people make choices like this, the entire global supply chain shifts to match consumer behaviour. So when more people demand ethically created products, more businesses create ethical products — because it’s good for their bottom line. A study published in the Journal of Manufacturing & Service Operations Management showed that consumers are willing to pay up to 10 per cent more for products from companies who are transparent with their supply chains. Businesses who are aware that ethical consumption is on the rise can take advantage of this. Marketing and packaging can highlight where your peanut butter comes from, how it rewards labourers, and what makes the package environmentally friendly.

Tech like QR codes can help tell these stories at the point of purchase. But for that information to really have an effect, you need to tell a story. As Barbara Crowther, the Director of Policy and Public Affairs for the Fairtrade Foundation explained in a live chat with The Guardian: “It is not just about functional information or education, but a genuinely emotional connection to the positive benefits that can be delivered.”

In September 2020, Australian confectionery manufacturer Darrell Lea announced they will be ditching palm oil in their products as a response to concerns from caring consumers. While palm oil is widely used in food production, plantation owners burn trees to clear land, leading to pollution and loss of animal habitat. “Continuing to use sustainable palm oil has always been an option for us,” Tim Stanford, the company’s marketing director told press “but the level of consumer enquiry we received encouraged us to explore a world without it.” To highlight their new stance, the brand released a video of an orangutan drumming to George Michael’s 1990 hit Freedom. It might be an intriguing visual, but it’s a vibrant example of the butterfly effect in action: in this case, vocal consumers leading to happier animals.

But what happens when brands don’t take these steps to ensure a sustainable supply chain? In these cases, another butterfly effect steps into the spotlight.

Organisations need to behave ethically throughout their supply chain – they can’t just do so at the front end through fair hiring practices in consumer-facing stores. More and more organisations are being held accountable for the actions of their suppliers, so today’s businesses must scrutinise product sourcing from top to bottom. Ethical scandals have seen wrongdoers exposed for failing to ensure safe working conditions, fair wages and labour rights of those within their supply chain.

The Nike controversy in the nineties presents a sobering example of damaging ramifications when poor supply chain management leads to unethical practices. After unethical working conditions at its overseas manufacturers were brought to light, protests and boycotts followed. This led to such a decline in sales that executives believed it would affect their bottom line far into the early 21st century. Then-CEO Phil Knight even admitted in a public speech that the Nike product had become “synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime and arbitrary abuse”.

As a result, according to a report in the New York Times during the controversy, the company said they planned to ensure that overseas manufacturers met strict US health and safety standards and would also allow labour and human rights organisations access to assess the quality of working conditions.

Find out how COVID-19 had a huge impact on supply chains

Discover the lessons learned from the pandemic

Find out more

When we shop online, we expect deliveries to arrive quickly. Spurred on by the consumer, we’re now living in a world driven by hyper-reactive logistics. Only 10 years ago, a package ordered online would have taken at least a week to reach the consumer. Today, next-day shipping is the norm. As a result of customer demand, Amazon has even patented technology for “anticipatory shipping”, where products are shipped before an order is even placed, rerouting it to a customer’s exact location when an actual order is received.

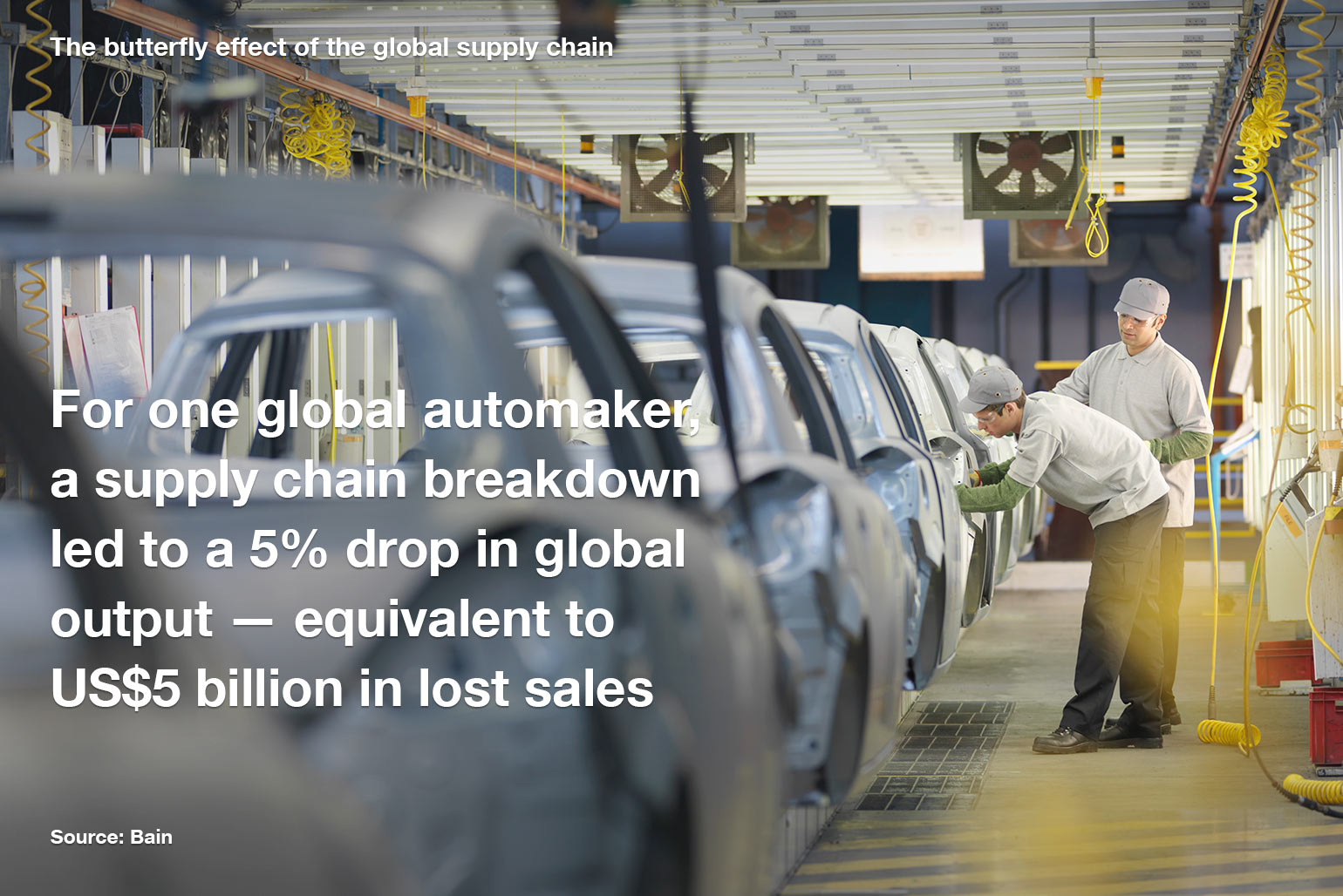

The complexity of modern supply chains has led to interdependencies that prove crippling when a single part breaks down. A car for example, consists of tens of thousands of parts, sourced from dozens of countries. Unsurprisingly, automotive supply chains are one of the most complex supply chains today.

This means that if a single component manufacturer in Italy shuts down, multiple automotive manufacturers they send parts to are impacted. When Thailand experienced a series of floods in 2011, a global automaker dependent on parts produced in the country saw a 5 per cent drop in global output, equivalent to USD5 billion in lost sales. The pandemic saw this happen at an unprecedented magnitude, with lockdowns worldwide forcing global manufacturers to reckon with the fact that entire supply chains can be at the mercy of one small moving part.

The importance of decentralised and diversely sourced supply chains presented itself most sharply when China went into lockdown in early 2020, as the coronavirus emerged. As a major global manufacturer, China produces 20 per cent of the world’s goods, the biggest single supplier. When factories in China were ordered to close, businesses worldwide saw their supply chains crumble, and were unable to meet demand. The resulting losses formed part of the disruption that plunged the global economy into what the World Bank terms “the worst recession since World War II”.

Building a supply chain that is ethical throughout can result in benefits that multiply several-fold. So what can businesses do to ensure supply chain integrity?

An obvious step is to ensure that those within the logistics ecosystem play by the rules. As a bank, one of the ways that we are contributing towards the building of sustainable supply chains is by taking a stand and only financing clients who demonstrate that they are working towards full transparency.

For example, we will not provide financial services directly to operations that grow, process or trade soy from the Brazilian Amazon or grow soy in the Brazilian Cerrado. We only work with companies that are committed to no deforestation and protecting native vegetation.

Supply chain visibility doesn’t just improve the quality of the company’s products and its productivity; an MIT Management study found that it also increased consumer trust in the brand. Given the growing capabilities of Industry 4.0 technology, from smart Internet of Things sensors to RFID tracking, there is little excuse for a lack of transparency across the supply chain.

Like any large-scale evolution, forging ethical supply chains is an involved and costly endeavour. Many businesses may cut corners for competitor advantage if these translate to cost-savings. But as companies like Patagonia, which reportedly brought in at least USD1 billion in revenue in 2017 and won the 2019 UN’s Champions of the Earth award prove, ethical behaviour can also be a form of competitive advantage. Put simply, ethical supply chains aren’t just good for the world — they’re good for the bottom line too.