Unpacking the role of carbon markets

What are the differences between mandatory and voluntary carbon markets, and how can organisation engage in opportunities across each?

This article summarises key themes and messages from our podcast “Carbon Markets: why do we need them”. Listen to the full episode on Apple or Spotify for the complete insights.

Putting a price on carbon has emerged as an effective way to help reduce or remove carbon emissions. In a recent podcast, “Carbon Markets: why do we need them“, Standard Chartered’s Chris Leeds, Head, Carbon Markets Development; and Lucy Palairet, Director, Carbon Markets Development explained the basics of both mandatory and voluntary carbon markets.

The starting point: mandatory carbon markets

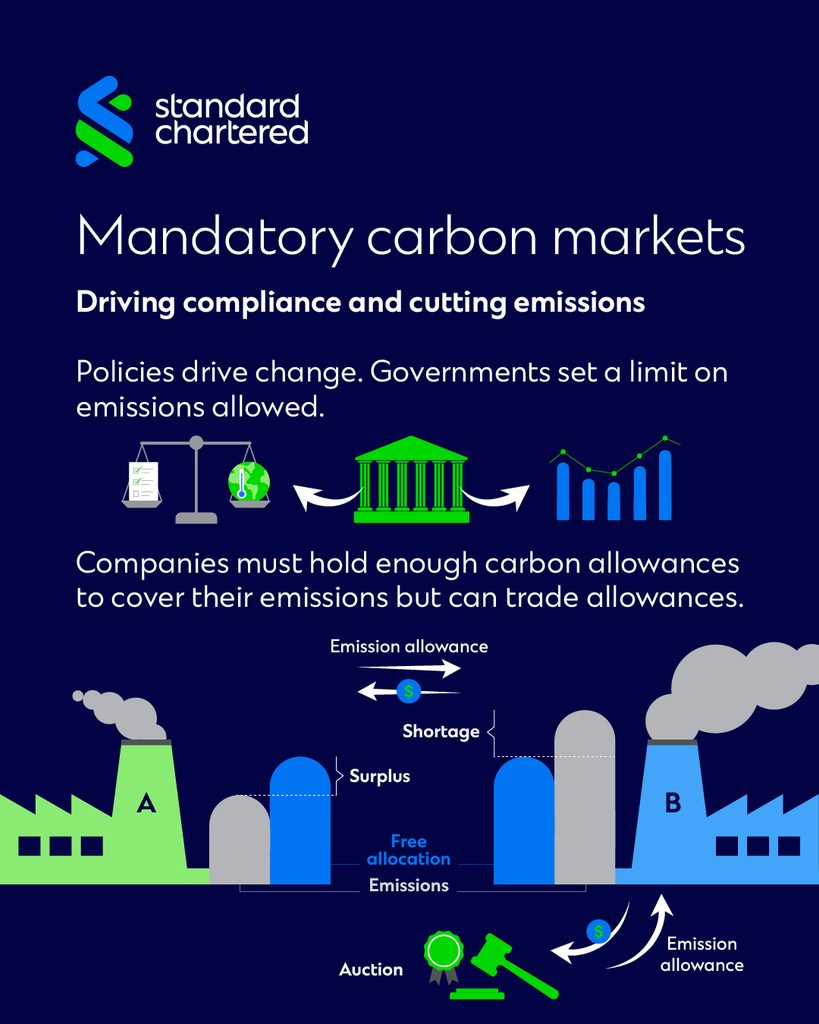

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the European Union’s groundbreaking Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the first economy-wide, annually tightened cap on emissions. Its effects have been dramatic, according to Chris Leeds, Head of Carbon Markets Development, Standard Chartered. By 2020 the ETS had helped cut emissions by 35 per cent from 2005 levels.

National, multilateral and global initiatives are providing new impetus. Most recently, in 2024, the UN’s COP29 summit agreed on mechanisms for a global carbon market, building on extensive work around Article 6 of the Paris climate accord. As a result, the number of countries with carbon pricing schemes is growing, with around 75 enforced compliance schemes globally subjecting some 25 per cent of worldwide carbon-emissions to pricing.

“These are matched by rigorous monitoring and third-party verified reporting,” says Lucy Palairet, Director, Carbon Markets Development, Standard Chartered. “Non-compliance carries significant penalties.”

Under the EU ETS, for instance, operators must purchase enough allowances to cover emissions. If they fail to do so, the scheme levies an inflation-linked fine of EUR100 per excess tonne of greenhouse-gas equivalent emissions, while the name of the penalised operator is publicly disclosed.

Cap-and-trade has been joined by other mandatory carbon-pricing mechanisms: baseline and credit schemes (companies below a set emissions level earn tradable credits) and carbon taxes (a direct levy governments impose on polluters).

Voluntary schemes: Offering a much-needed boost

Many companies have also chosen to go beyond these mandatory obligations by buying credits from projects that reduce or remove carbon in the atmosphere, according to Palairet.

The drivers for such voluntary carbon markets are varied, she adds, nothing that they range from reputation enhancement and stakeholder engagement to talent appeal and access to concessional green finance, to readying for future mandatory regulations. “Voluntary and mandatory schemes can even work in tandem, creating hybrid markets,” she says.

Singapore, for example, levies a carbon tax of SGD25 per ton on qualifying entities, but five per cent of their exposure can be covered by international carbon credits sourced from high-quality voluntary schemes. “Likewise, China’s emissions trading scheme allows five per cent of a company’s exposure to the scheme to be covered by a specified carbon credit,” notes Palairet.

She believes this hybrid ‘additionality’ is key to providing an important boost to global decarbonisation efforts, however, voluntary carbon credits must reduce or remove carbon in ways that would not have occurred otherwise, and this must be validated. “Accreditations and standards have emerged to ensure exactly that.”

Rising standards: Key to unlocking capital growth

Bodies like the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Markets (ICVCM) are working to bring consistency and credibility to the market with an aim to scale up funding to high-impact climate solutions by creating an ecosystem that prizes and builds integrity, trust and transparency. Bolstered by UN rules, ICVCM’s 10 Core Carbon Principles (CPPs) are designed to identify additionality, permanence and other signifiers of high-quality carbon credits. “The CPPs are a critical shift in a market seeking to enhance price transparency, improve price discovery, reduce hesitancy, and attract more capital,” argues Leeds.

Financial institutions are also playing a role. Palairet notes that Standard Chartered only uses credits from registries with strong frameworks around carbon accounting, which also cover social and environmental risks. Standard Chartered subjects each registry to the same Environmental and Social Risk Management frameworks it uses internally.

Alongside establishing such guardrails, a second and related challenge is the lack of standardisation, and thus market clarity, among the wide diversity of abatement projects. Again, however, the UN’s international leadership is aiding in this regard.

“Everybody’s talking the same language, and the voluntary carbon markets are now really working hard to align themselves with the standards that are being developed by the UN,” says Leeds. “That’s really, really important.”

Carbon markets are a fundamentally good idea for reducing or removing emissions and channeling investment towards sustainable solutions, believe Leeds and Palairet.

“Ultimately, in terms of the emissions targets under the Paris Agreement, we’re facing an approximately 6.3 billion tonne carbon deficit,” says Palairet. “With greater standardisation, carbon markets can really help address this gap, building confidence in the market, scaling it up and getting us all to where we want to be in terms of emissions.”

Our latest insights

What will accelerate SAF scale-up?

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is key to decarbonising aviation but faces economic and policy hurdles. Explore …