The hotspots within the sustainable debt space

Sustainable debt is one of the fastest-growing asset categories in the world of finance, but within that broad category exist many types of debt instrument – some of which are attracting more interest than others. From the many varieties of sustainable debt, here we assess those that are now powering the expansion of the asset class and helping make sustainability a fundamental part of the debt issuance and investment process.

The world of green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds is growing very quickly. Standard Chartered expects issuance of such bonds to reach USD1.7tn in 2022 – a jump of 52% from the previous year – and USD4.2tn by 2025. If our forecast proves accurate, GSSS would represent around one-third of global bond issuance by that point, propelled by ever-more exacting and far-reaching regulations and standards around sustainability.

Most of the green debt currently being issued comes in the form of use-of-proceeds instruments such as green bonds – the “G” in GSSS. These refer to any kind of debt instrument where the proceeds are used exclusively to fund projects that have a clear environmental upside. In other words, they are activity-based. People often think in terms of solar or wind power installations, but green bonds can be used to finance everything from biodiversity and natural resource conservation to pollution control.

There is much more to GSSS than green bonds, however, and nor are all forms of sustainable finance attracting the same degree of investor interest. Take transition bonds for example. They finance projects such as a natural gas power plants that are cleaner than coal but don’t count as green energy.

Interest in transition bonds sputtered in 2021, with less than USD5bn of issuance. This came amid signs of investor scepticism about whether the projects and sectors eligible were genuine efforts at decarbonising the world economy, or were rather a “transition-washing” attempt.

Proving much more popular are sustainability-linked instruments, the final “S” in GSSS (not to be confused with sustainable bonds). Unlike green bonds, sustainability-linked assets are not use-of-proceeds instruments, but general-corporate-purpose ones. The finance is not tied to a particular project, but to the overall performance of the issuer in terms of hitting sustainability targets.

Standard Chartered expects these sustainability-linked instruments to be the fastest-growing components of the GSSS universe this year. In 2021, just two years after Italian energy group Enel launched the world’s first sustainability-linked bond (SLB),1 annual SLB issuance ballooned to USD109bn. In 2022, we expect that figure to as much as double, with the potential to cross the trillion-dollar mark in 2025, making up one-quarter of the entire GSSS market by that point.

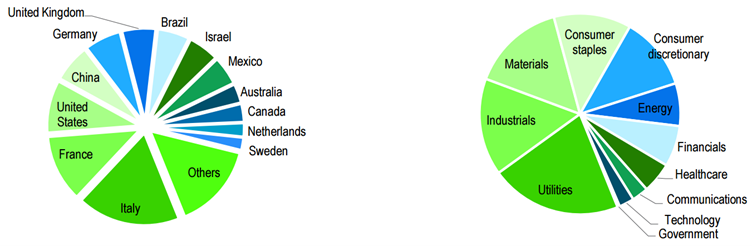

Figure 1: SLB issuance in 2021 came from a diverse set of sectors and countries

Sources: Bloomberg, Standard Chartered

This booming demand is mirrored by the market for sustainability-linked loans, with issuance soaring to USD428bn in 2021 from USD125bn the year before. While Europe is the epicentre for sustainability-linked issues, emerging markets are already well represented – 28% of the total issued in 2021 – and are likely to become more so in future, given that they are where the finance gap is widest, with progress towards decarbonising their energy sectors in most cases lagging that of developed markets.

What is driving this preference for SLBs? Flexibility is the main draw. Corporates and other issuers can use the finance raised for general purposes, rather than ring-fencing it for an approved project. Instead of carving out specific ESG projects, the issuer is incentivised to meet corporate-level sustainability improvements. This assists investors when it comes to transparency, particularly as performance requirements and covenants get firmly established and become more easily and regularly monitorable.

The International Capital Markets Association defines an SLB as a bond in which the issuer commits to specific, time-bound improvements to key performance indicators (KPIs) relating to sustainability.2 These KPIs are ideally ones that can already be found in the issuer’s annual reports, so improvements can be assessed against a historical baseline. Those improvements should go above and beyond what might reasonably be viewed as a “business as usual” trajectory, to demonstrate real gains.

For example, a EUR1.25bn SLB launched by French personal care giant L’Oréal in March 2022 was based on KPIs related to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and making greater use of recycled and biobased packaging materials.3 If the issuer hits or misses these targets – as verified by an external provider – this then has consequences for the bond; usually, a variation of the coupon, with the rate of interest linked to sustainability performance. Most of the SLBs issued to date have used emissions controls as their targets, but there is no reason why a broader range of metrics cannot be used, for instance touching on social or governance factors.

While the bulk of sustainability-linked issuance is from the corporate sector, sovereign SLBs have now also become a reality. In March 2022, Chile issued the world’s first ever such sovereign bond, with KPIs tied to the country’s emissions and renewable energy commitments under the Paris climate change accord.4 The USD2bn 20-year SLB received bids from a diverse and global range of investors and is now listed on the London Stock Exchange’s International Securities Market and Sustainable Bond Market.5

We foresee this shift towards general-purpose debt instruments as a key trend within the rapidly growing GSSS segment, and one that may presage a broader shift over the medium to long term. It may be the case that soon, instead of sustainability being regarded as something niche or optional, it becomes a fundamental part of the debt issuance and investment process – one that all participants are expected to adhere to in order to participate within the mainstream of financial commerce.

This report takes key themes from a Standard Chartered research report, “Sustainable debt market – Up, up and away”. Read the full report here.

For more information about Standard Chartered’s sustainable finance capabilities, visit: Sustainable finance.

References:

1 https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/8a104da8/sustainability-linked-bonds

2 https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/June-2020/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-June-2020-171120.pdf

3 https://www.loreal-finance.com/system/files/2022-03/2022%20L%27Oreal%20Sustainability-Linked%20Financing%20Framework%20Second-Party%20Opinion_0.pdf

4 https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/world-s-1st-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bond-issued-by-chile-69226229

5 https://www.londonstockexchange.com/discover/news-and-insights/london-stock-exchange-congratulates-republic-chile